Flagstaff, Route 66 and the Green Book

For nearly 30 years, multiple editions of The Travelers’ Green Book provided African Americans with advice on safe places to eat and sleep when they traveled through the Jim Crow-era.

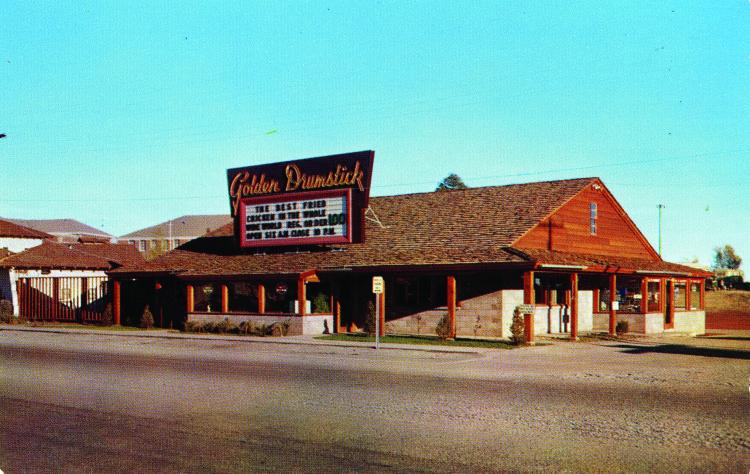

Flagstaff, like other northern Arizona cities and towns became part of the Route 66 community when the road was established across Arizona in November, 1926. The road only added to northern Arizona’s vacation, transportation and commerce activities. Flagstaff responded by establishing the All-Indian Pow Wow in 1929, and during the next decades, local businessmen created tourist destinations, and tourism-related businesses including hotels, motels, cafes and gas stations to service the new road-based travelers.

Flagstaff, like Holbrook, Winslow, Williams Ash Fork, Seligman and Kingman welcomed tourism as an economic engine for their towns, and saw their towns evolve for these new businesses. The towns grew not around the railroad station, that other economic engine (as in the past), but along Route 66 to catch those tourists as they hit town.

Soon after the designation of federal highways (like U.S. 66), New York Postman Victor Green hit upon an idea. To make travel safe for Blacks who traveled by road (often to avoid segregation), that they needed a directory that would ensure they could travel without “embarrassment”. The Negro Motorist Green-Book was born. First published in 1936 and all the way up through 1963-64, past the Civil Rights Act (1964) and Green himself, who died in 1960. The earlier editions of Green’s book focused on the urban east, and ultimately expanded to include most of the United States, and even becoming international in the 1960s. Each edition features an alphabetic list of businesses by state and city that catered to or included Black customers, and often included articles on travel and social issues around travel. The reality is that the Green Book assisted Black travelers to be able to locate businesses that were not “Whites Only” or where they could safely be, especially with the advent and creation of so-called “Sundown” towns.

Green’s book while successful, and the most well known was not unique however. Other guides like Travelguide: Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation listed many of the same businesses, and others not listed in Green’s book.

What does the Green Book (and similar titles) reveal about Flagstaff? Well, first that Flagstaff doesn’t make any of the pre-World War II editions. For Arizona Route 66 towns and cities, Kingman first appears in the Green Book in 1956, and three places in Flagstaff appear in the 1957 edition: The Park Plaza Motel, the Nackard Inn and El Rancho Motel- which populate the Green Book to the end of its production run.

The U.S. National Park Service turned up other Flagstaff sites for Black travelers from other sources. They include Andy Womack’s Pink Flamingo, the DuBeau Motel, the Vandevier Motel and Restaurant, and a rooming house on South San Francisco Street for a total 7 facilities for overnight travelers and one café- the Greyhound Bus Station.

Of these businesses, all were generally south side, and along 66 alignments with the exception of the Vandevier, and the Greyhound station, both of which were north of 66 and the railroad tracks. Of these properties, part of the Park Plaza lives on as a dormitory at NAU (Roseberry Hall) and was built in partnership with ASC to house students off-season; the Nackard Inn is now the Downtowner (on the 1926-1935 alignment of Route 66 along Phoenix Avenue and Mike’s Pike). The El Rancho and the Pink Flamingo are gone and were once where Barnes and Nobles is now located at South Milton and West 66. The Du Beau is still a functioning motel on the corner of Phoenix and South Beaver Street. The Vandevier Motel and restaurant is now apartments located at the corner of Sitgreaves and Santa Fe. The Greyhound Depot/café is now AZ Music Pro, at 122 East Route 66.

The Green Book is now the subject, or at least the foundation for a number of novels, articles, documentaries, podcasts and a notable feature film, exploring that relationship between America pre-1964 and Jim Crow law and culture that denied right and a equality to all. The publisher who is re-issuing the historic editions of the Green Book (About Comics) said:

“When you read a copy of the Green Book, you're kind of hoping that it would be filled with explanations of why there are such limitations, what's going on, and angry invective railing against the injustice, but when you see it with its simple listings, ads, and little articles, you realize that it is far fiercer indictment without those things. To expect this book to announce the injustice of it all is like expecting a fish to say "I was swimming, in the water." The water doesn't need to be mentioned. The water is everywhere, it is assumed. There was not a single person who bought the Green Book back in 1940 who didn't know why it was needed; they were just glad to have it available.”

About the Author

Sean Evans & Gretchen McAllister

Sean Evans is a librarian and archivist at the Cline Library at Northern Arizona University. Sean has a long and complicated interest in Route 66 and the broader story it tells of our regional and national history. Route 66 is both his scholarly area of interest, and his irrational outlet. Gretchen McAllister is an Associate Professor of Teaching and learning in the College of Education at Northern Arizona University. 15 years ago she fell in love with the stories of Route 66 and the ways that this road brought people together. Today she continues to work with teachers and their students in learning those stories. An ongoing curricular website on the multiple perspectives along the Mother Road is available at