Pluto is the official state planet of Arizona

What does Pluto have in common with the Grand Canyon, saguaro blossom and cactus wren?

What does Pluto have in common with the Grand Canyon, saguaro blossom and cactus wren? They all are official symbols of Arizona now that state law declares “Pluto is the official state planet.”

Pluto was discovered by Clyde Tombaugh at Flagstaff’s Lowell Observatory in 1930.

Pluto now holds a place among those other state icons. Arizona’s nickname is Grand Canyon State. Saguaro blossom is the official state flower. Cactus wren is the state bird. (The list goes on, with Sonorasaurus as the state dinosaur and lemonade as the official state drink.)

The story of Pluto’s discovery was so impressive to state lawmaker Justin Wilmeth, a representative from Phoenix, that he introduced the legislation designating the state planet in early 2024.

House Bill 2477 passed both the House and Senate nearly unanimously, and Gov. Katie Hobbs signed the bill into law March 29.

Having Pluto designated as the state planet highlights the astronomy research and engineering work that continues to take place at Lowell Observatory and across the state.

It also reminds visitors that Flagstaff is a major astrotourism destination. Not only does Lowell welcome more than 100,000 visitors a year, but Flagstaff in 2001 became the first designated International Dark-Sky City. Flagstaff has a strong lunar legacy, too. Every astronaut who has walked the moon trained in Flagstaff using destinations like Meteor Crater, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument and Grand Canyon National Park to prepare for space.

Pluto was the last of the classical nine planets to be discovered and rose to pop culture stardom in 2006 when the International Astronomical Union decided that, for technical reasons related to its gravitational pull, it should be reclassified as a dwarf-planet and no longer be counted among full-fledged planets.

The International Astronomical Union considers objects like Pluto that do not have enough gravitational pull to clear their region of other objects such as asteroids and comets to be dwarf planets. There are five known such dwarf planets, and the discovery and reclassification of some of them played a role in Pluto’s reclassification.

The bill signed into Arizona law makes no mention of the dwarf-planet reclassification. Two other dwarf planets were discovered by California researchers, but for now Arizona is the only state to claim an official state planet.

“It is a planet. It’s just a dwarf planet, like Jupiter is a giant planet and the Earth is a terrestrial planet,” said Dr. Amanda Bosh, a planetary scientist, astronomer and chief operating officer at Lowell who testified at the Legislature in support of the law. “So, it didn’t stop it from becoming the state planet.”

“What the bill does is really bring awareness that we do science here in Arizona,” she said. “We discovered amazing things that have really impacted the field, and this is our planet.”

At Lowell Observatory, visitors can see the historic, nearly 100-year-old astrograph used to discover Pluto. At night visitors can view celestial objects through modern telescopes with assistance from experts.

Lowell Observatory also will open the Marley Foundation Astronomy Discovery Center in November 2024, offering a variety of interactive exhibits to help visitors explore space.

Sitting on a hilltop over historic downtown Flagstaff, Lowell Observatory is an ideal place for professionals and hobbyists to view the stars. The Milky Way is visible from downtown thanks to the city’s work to curtail light pollution.

Lowell Observatory also offers visitors the opportunity to learn the fascinating story of Pluto’s discovery that motivated Wilmeth to introduce legislation designating it the official state planet.

Percival Lowell established the observatory in 1894, initially to search for life on Mars. While that didn’t pan out, Lowell came to know the other planets well.

In 1902, Lowell theorized the existence of a ninth planet he called “Planet X,”’ based on the orbits of the other planets. In 1905, Lowell began searching for a ninth planet.

This was a bold proposition. Most other planets in our solar system – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, were all visible to ancient people in the night sky, leaving their precise moment of discovery unknown. Only two other planets had been similarly discovered, both in Europe. Uranus was discovered in 1781, and Neptune in 1846. So it had been nearly 60 years since anyone had found a new planet when Lowell set out on his search.

Lowell in 1911 purchased a piece of equipment called the blink comparator, which is still on display at the observatory. This allowed astronomers to compare photographic plates from the same point in the sky over the course of different nights to see if any points of light moved, indicating they could be something other than a star.

Lowell died in 1916, but his work carried on. A young farming man from Illinois and later Kansas named Clyde Tombaugh was inspired by Lowell and other astronomers. He built his own telescopes and sent drawings of Mars to researchers at Lowell asking for comments. Instead, they offered him a job, which he started in 1929. He was tasked with searching for the so-called “Planet X” that Lowell had theorized.

The work was painstaking, not only in comparing photos from one night to the next to look for moving points of light, but even to calculate where in the sky to aim the telescope and photography equipment.

“Back then, computers were people, oftentimes women, who would run calculations by hand,” Bosh said. “From those you could figure out, ‘We should be looking over here.’”

Less than a year later, in February 1930, with the help of the comparator, Tombaugh discovered a point of light that moved through the night sky. Staff at the observatory worked feverishly to confirm the finding and study its orbit before making an official announcement of a new planet on March 13, 1930, which would have been Percival Lowell’s 75th birthday.

Lowell staff chose the name Pluto, with credit to an English schoolgirl named Venetia Burney who suggested the name because the planet was described as cold and distant, like the underworld ruled by the mythological god Pluto.

The observatory and Flagstaff have continued to make significant contributions to astronomy, including discoveries related to Pluto.

Charon, the largest of Pluto’s five moons, was discovered from pictures taken in Flagstaff at the U.S. Naval Observatory and Lowell Observatory researchers were involved in the discovery of Pluto’s atmosphere.

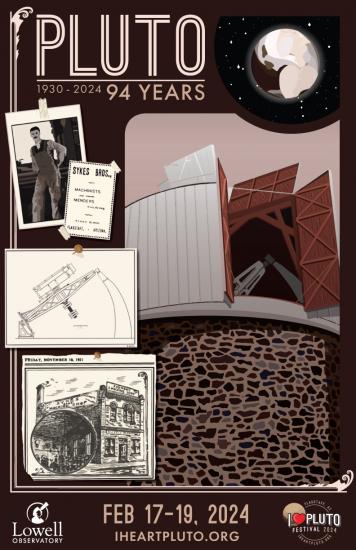

Today Pluto remains close to the heart for Flagstaff residents and visitors. Each February, the city commemorates the discovery with the popular I Heart Pluto Festival, which is celebrated with scientific talks around town and Pluto-themed specials at local restaurants, breweries and bars.

Start planning your astrotourism trip by ordering a visitor guide from Discoverflagstaff.com.

About the Author

Discover Flagstaff

Send An EmailDiscover Flagstaff features travel information for visitors to Flagstaff, Arizona and regional attractions like the Grand Canyon, Sedona, Navajo Nation and Route 66.