Scenic and Cultural Jaunts in the Flagstaff Vicinity That Are Not the Grand Canyon

Author and former Flagstaff outdoor instructor and wilderness guide Michael Engelhard describes lesser-known outdoor adventures in Northern Arizona.

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

As you drive south from the Cameron Trading Post toward Flagstaff and the southwestern rim of the Colorado Plateau, cinder and jagged basalt oust the Painted Desert’s sinuous shale. The blond grasslands transected by Highway 89 appear torched, hardened with lava veins, blackened with pustules and scabs like charred skin. While this area of the North American tectonic plate was sliding across a hotspot in the planet’s mantle, molten rock pushed through fissures and cracks. It came oozing to the surface or mixed with gases and lobbing fiery mayhem a mile high. With the crust steadily inching northeastward, volcanoes boiled up, geysered, and fizzled, and the San Francisco Volcanic Field stretched into a fifty-mile belt of more than 600 vents.

Near the crest where the highway starts dropping into Flagstaff, Sunset Crater marks this ground’s most recent violent birthing, which occurred during the late fall or winter of 1064–1065 C.E. The event for miles around scorched prehistoric pit houses and filled them with cinders; lava undoubtedly mantles others, a scattered Pompeii. No human bones were found at such habitations, so it appears that the local Sinagua living here at the time had ample warning. Major John Wesley Powell in 1892 named the 1,000-foot-high, symmetrical cone, for its cap of rust-colored, oxidized, scoria spatter, deposits that make it appear bathed in evening light. When actual sunsets intensify the tinted glow, it seems as if the rim were about to ignite.

This national monument can be explored on short walks on groomed paths. Please don't hike off-trail, because fragile desert vegetation — including a penstemon that grows nowhere else — and even volcanic features, are easily, irreparably damaged. One of the highlights among lava bombs and cinder fields is a sinkhole cave so insulated that it preserves ice for much of the year. The Hopis consider this place sacred: the lair of the North Wind.

Wupatki National Monument

Easily combined into a loop drive with the Sunset Crater excursion, Wupatki formed an ancient crossroads on the banks of the Little Colorado River, a major branch of the Grand Canyon. The Little Colorado here runs only seasonally, depending on rainfall and snowmelt. Wet or dry, it has attracted people for at least 11,000 years. Some Ice Age hunter lost a leaf-shaped, fluted spear point on the prairie close by, a dandy blade for killing mammoths; the bones of one surfaced not far from here. The obsidian came from many miles away. The lower gorge enfolds the Sipapu, a travertine dome spring from which the Hopis climbed after three previous worlds had been destroyed. They were set adrift in the fourth and final world. After they settled down, the Little Colorado connected Homolovi and the Hopi Mesas to the north with Wupatki, the Grand Canyon, and points south. Goods, individuals, and ideas trickled both ways, according to season and want. Tokens of far-flung trade — Mexican copper bells and scarlet macaws, seashells from the Pacific — traveled as far as Wupatki. The hundred-room pueblo squats on a rock knoll. Its Mesoamerican-type ball court is the northernmost of its kind. Between 500 and 1225 CE, when the inhabitants permanently abandoned Wupatki, evicted, most likely, by drought, thousands of people lived there or within a day’s walk in nearby pueblos such as Wukoki and The Citadel. It is forbidden to explore the ruins on your own, but the visitor center schedules ranger-guided walks.

Another earth cavity deserves notice on this lion-skinned plain, making it famous, drawing pilgrims, as yet another home of a wind god. Near the pueblo, a large tectonic fissure, one of several in the region, inhales and exhales through a blowhole only a few inches wide. As the outside temperature and barometric pressure change, air rushes through the opening at up to 30 miles per hour, forceful enough to levitate a plastic bag or to whip back the long hair of a person bending over the subterranean gale.

San Francisco Peaks

Qualifying Flagstaff as a mountain town, six San Francisco Peaks crowd around their eminence, Humphreys Peak, which soars 12,637 feet above town. The climate on top of the state’s highest mountain can be arctic. The vegetation resembles tundra. In 1889, jack-of-all-trades scientist Clinton Hart Merriam developed his “life zones” concept on these slopes, the idea that characteristic plant and animal communities change with elevation — and 1,000 feet of elevation in this sense also roughly equal 300 miles in latitude. The panorama that rewards intrepid hikers on the final ridge after an almost 5-mile climb unscrolls to encompass the Painted Desert; distant Hopi mesas; canyons near Sedona; and both rims of the grandest of canyons. Conversely, the range perched on the margins of the Colorado Plateau can be seen for nearly 100 miles from any direction. The peak is a stratovolcano, like Japan’s Mount Fuji, steeper than shield volcanoes and estimated to have once reached nearly 16,000 feet. After winter storms, avalanches scour its gullies and ravines. Within minutes, rain can corn into hail, bouncing off rocks crusted with lichens. Lightning commonly strikes during summer afternoons. It is no surprise that weather gods are thought to dwell on these heights.

No fewer than 13 tribes hold sacred this blown-top upthrust, a place, for the Yavapai-Apache Vincent Randall, “where the Earth brushes up against the unseen world.” It’s a pilgrim destination, seasonal home of Hopi rain-bearing holy beings, one of four pillars that prop up Diné (Navajo) homelands and the cosmos. Sadly, the Diné name, Dook’oosłííd, “Its Summit Never Melts,” no longer fits. According to Hopi beliefs, Nuvatukya’ovi, the “Place of

the High Snows,” is the home of a host of deities, one of whom is in charge of cold weather and the white gift that saturates the earth for the next year’s crops. The Kachina Peaks Wilderness honors the Hopi elemental spirits and the tribe’s links to this mountain fastness.

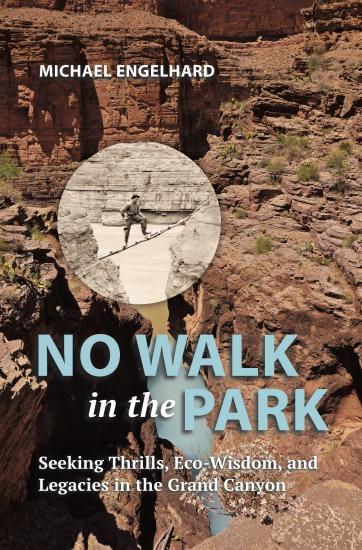

View No Walk in the Park: Seeking Thrills, Eco-Wisdom, and Legacies in the Grand Canyon on Amazon.com

About the Author

Michael Engelhard

Trained as an anthropologist, Michael Engelhard worked for 25 years as an outdoor instructor and wilderness guide in the canyon country and Alaska. His most recent book recounting his adventures in this region is No Walk in the Park: Seeking Thrills, Eco-Wisdom, and Legacies in the Grand Canyon. View his website: https://michaelengelhard.com